Deployment Notes

At this stage, the team of GDI Estonia at the University of Tartu has completed the deployment phase of the Genomic Data Infrastructure (GDI) project. It is now focusing on achieving operational status by the end of 2026. Since 2023, the team has gathered expectations and requirements, as well as evaluated various tools to understand conditions for establishing a local GDI node that connects to the central GDI User Portal. This document is a distilled report about the deployed GDI Estonia node solution and the shaping stories behind that.

Understanding the Node

Existing technical infrastructures (regarding genomic data) and financial resources to sustain them are quite diverse across the countries, which leads to people having different perspectives about what a node in the GDI should cover. The situation in Estonia before the GDI was and still is quite operational. There are a few organisations that produce digital data from genomic samples. They have different aims and quality processes, meanwhile data sharing is quite restricted (typically, subject-level consents are required when the Human Genes Research Act does not cover the case). However, the game-changer for data sharing is the European Health Data Space (EHDS) Regulation, which requires institutions to make their data available to others under certain circumstances.

So the key information about the current situation is as follows:

- Institutions already have their genomic data management in place.

- Institutions want to retain their data, as this is an integral part of their everyday work.

- Institutions are interested in safe data sharing solutions due to EHDS.

On the other hand, Pillar II in the GDI project demonstrated that the technical expectations to the node revolve around:

- dataset management (FAIR Data Point – dataset catalogue);

- dataset discovery (filtering datasets, variants lookup over GA4GH Beacon API);

- exposing aggregated properties (population-level allele frequency lookup using GA4GH Beacon API).

Putting together the picture of the current situation and the expected services, the team of GDI Estonia defined the local GDI node as a service for exposing national datasets (metadata) to the European User Portal. The node can also prepare a research environment with some (potentially minimised) data for researchers. However, the node is not expected to host the original genomic data files on behalf of data providers who already have established their own data management processes. Since storing large files with required backups is an expensive service, the node can suggest HPC as a potential service provider; however, in general, it’s the data provider’s task to determine the funding and the solution.

The shape of the GDI Node in Estonia is also greatly affected by the funding issue. The representative of GDI Pillar I, Ministry of Social Affairs, expects that the GDI-specific services will be funded by the EDIC. However, the ministry is also not satisfied with the high EDIC membership fee, which may deter potential members, including Estonia, from joining EDIC. Meanwhile, the ministry is unable to find any national funding, which means that the GDI node will be running on low resources. This has also been one of the primary motivators for optimising business processes and the technical solution of the GDI node.

In conclusion, a GDI node can be a fairly lightweight infrastructure that just manages dataset catalogues, supports genomic variant lookups, but overall the node is mostly a local coordination point for central GDI services and for researchers who want to access some datasets.

Understanding the GDI Services

The minimum of the required GDI node services, as agreed between the member states of the GDI project:

- FAIR Data Point dataset catalogue service

- Beacon API serving allele-frequency requests from the GDI User Portal

- Beacon API serving “sample count for a variant” requests from the GDI User Portal

The primary goal of the GDI is to enable discovery of existing genomic data and requesting access. Meanwhile, at the national level, the nodes need to support local genomic data producers with the know-how on definining datasets, transfering the metadata to the node, and later also participating in the data-access approval process. The data providers are from typically from research and medical sectors.

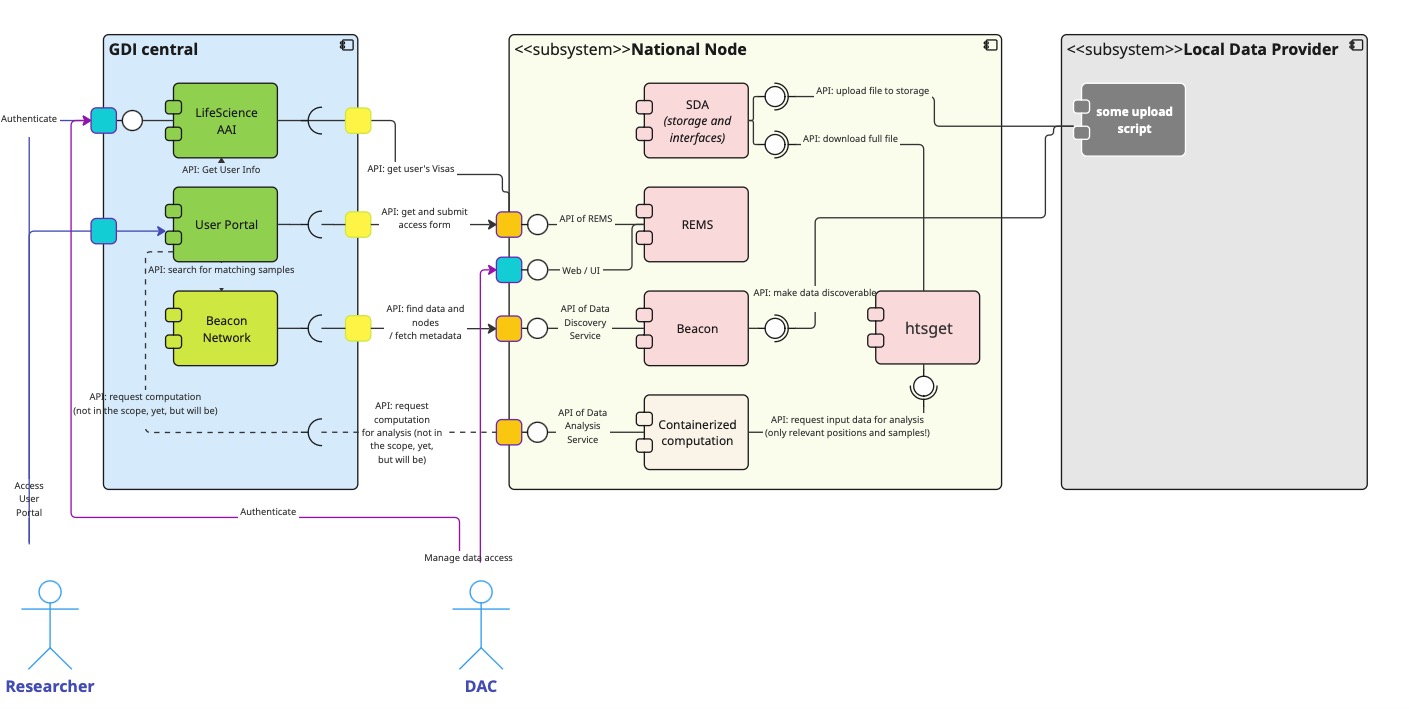

However, before proceeding to them, we know that the initial technology stack (“the starter kit”) comprised more services, so let’s compare first how we handled them in the Estonian node. The following architecture image represents the architecture that was initially expected back in 2023:

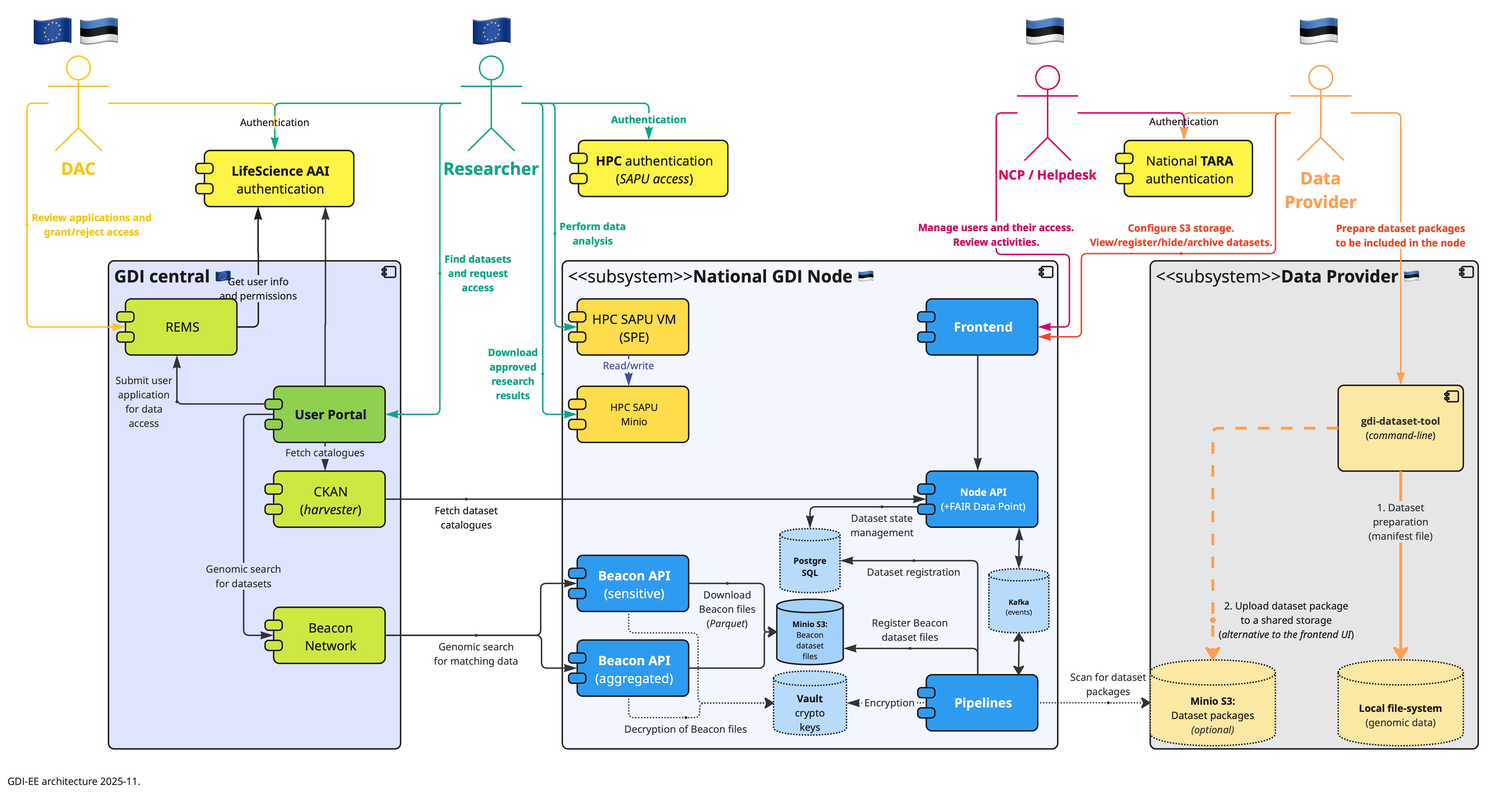

REMS – the permission service

REMS enables users to request access to one or more datasets. Upon receiving a researcher’s application, the back-office runs the “Data Access Committee” (DAC) business process to either approve or reject the request. Upon approval, REMS automatically grants a technical Visa for the requested resource to the researcher’s user.

After analysing the desired workflow for approving a data access, the team realised that it’s much more complicated and it requires more human effort to complete the process. Since the process is not well-defined (EDIC is still not final, and no one has tested the “production-ready” data-access requesting), it is too early to cast the rules into lines of software code. Therefore, the best to offer now is a human-based email-messaging process with documents to be signed – until the requirements and corner cases of the workflow are fully resolved.

Meanwhile, registration of data-access requests in the central REMS remains a good starting point for the workflow and potential users. The process should be ideally unified for all nodes, and therefore hosted centrally for the convenience of researchers. As for granting the actual permissions (in systems), it should be implemented in the nodes, as the research infrastructure is physically there. In the Estonian node, setting up research environment permissions is the task of the National Coordination Point (NCP) in collaboration with the local High Performance Computation Centre (HPC), which handles the technical part.

SDA – the registry of dataset files

The biggest issue for the node is obtaining sustainable funding for maintaining the technical infrastructure and the storage of big genomic data. When the team of GDI Estonia compared the local price list, it became clear that keeping the genomic data online (on S3) every day of the year is 2.5 times more expensive than tape storage. Meanwhile the data might not be actively used for months.

The team also realised that the data-access approval process will also take days, if not weeks, to complete. Therefore, the data providers have plenty of time to restore selected data from their tapes, run minimisation steps, produce the file format that the researcher actually needs, and transfer it to the research environment. Of course, this process is time-consuming and labour-intensive, but it’s the most economical and flexible solution for a business process that is initially estimated to occur rarely (a few times per year).

Delegating the file storage issue to the data providers also has the benefit that they don’t lose control over their data management, and they are not forced to adapt to the interfaces of the node’s file storage. Thus, nationally, it was a win-win decision for all the stakeholders to not deploy the SDA stack as a part of the GDI node.

HTSGET – the filter-service for genomic data

Since data storage interfaces were not established in the Estonian node, introducing the HTSGET service became redundant. There were also concerns that data minimisation over a streaming API might be slow and prone to interruptions. In addition, the team was not confident that an average researcher would prefer to filter data using the HTSGET API – there are tools that are more familiar to them. It made sense to switch to traditional file-based data delivery instead. Meanwhile, the data providers have the know-how and control over the data minimisation before delivering the files to the research environment.

TES – task-execution in a secure environment

The Task Execution Service (TES) introduces an API-based computation task submission and monitoring system. However, this kind of approach to secure processing environments (SPEs) raises some controversial questions that eventually require a new team of experts that Estonia currently does not have:

- How do we support our users (training, tech support)?

- How can we trust the container images referenced by the tasks?

- How do we ensure that tasks do not interfere with each other and their data?

- How do we ensure that tasks cannot communicate with each other or other services in the local network?

- How do we collect results and manage disk space?

- How do we approve data exports?

Despite its straightforward approach, running a TES-compliant SPE service requires maintaining a dedicated expert-level team. Without active funding and a user base, developing and providing this service is infeasible.

However, HPC at the University of Tartu is already offering a VM-based secure data analysis environment solution SAPU, which is different from TES:

- Each research project will get a dedicated VM, where security is hardened.

- The VM running on Linux is configured by HPC admins with the tools requested by the researcher.

- There is a graphical desktop user interface that is familiar to most users.

- The input data is stored in an S3 bucket (appears as a folder on the VM), where data providers can upload to themselves.

- The data, that the user wishes to export, is saved to another S3 bucket (appears as a folder in the VM), where the data provider can review and approve it for export.

- The approved export data is made available to the researcher for download over an S3 API and UI.

Although setting up a VM for secure analysis takes time, and it does not provide an API for federated computation, it is still the best sustainable technical solution Estonia has to offer at this stage. There is a well-defined and yet simple business process behind analysing sensitive data on SAPU VMs and the process includes data providers, researchers, and HPC staff. A VM might not offer the ultimate technical capacities of the HPC, however, it should cover at least the needs of the majority of research scenarios. In future, it might be easier to develop dedicated genomic data services, if the platform gains attraction and user expectations become more clear.

Beacon – genomic database with an API

The primary issue with deploying a Beacon server with genomic data is its sensitivity. Although researchers would gladly use all the data that the Beacon data model prescribes, gathering, maintaining, and controlling access to the data appears to be a complex task.

Another issue with the Beacon2 PI solution is data management, as it relies totally on MongoDB, which already structures the data according to the Beacon data model. However, the team was uncertain about MongoDB being the right choice for storing big data (genomic variants), building indexes, and enabling data lookup.

During the GDI project, the team of GDI Estonia realised that the User Portal would not provide a complete user interface for all the features that Beacon can offer. Only a few data-exposing endpoints had to be supported:

- datasets (general information about datasets)

- allele frequency information for a variant (public and based on aggregated data);

- variant lookup and reporting the number of matching samples (restricted and based on individual data).

Reverse-engineering the Beacon client (User Portal) code, the team determined the required input parameters and output fields. Thus, a custom “minimal” Beacon solution, that supports the Beacon framework and the /g_variants endpoint, was developed. Note that the custom endpoint handler does not even support all the query styles defined by the Beacon specification – just the query style that the User Portal uses.

The custom-developed solution to Beacon data management are file-based tables of variants and allele frequencies. It is easier to manage files than database records, as managing dataset visibility can be handled at the file-system level. In GDI Estonia, the tools extract Beacon data (variants and allele frequencies) from VCF files and store them in several Parquet files, a big data file format which covers data compression, encryption, and fast lookup. These Parquet files are stored in an S3 bucket, and the resource-path also reflects the dataset ID, reference genome, chromosome, and range of positions. The system tracks dataset visibility in a separate relational database – this information restricts the list of Parquet files being searched.

The directory structure of the Parquet files in the Beacon:

/{reference_genome} # Ex: GRCh37, GRCh38

/{DATASET_ID} # Ex: GDIEE20251021473903D

/allele_freq-chr{CHR}.{block_number}.parquet # AF Beacon files

/variants-chr{CHR}.{block_number}.parquet # Sensitive Beacon files

Here, CHR is a number from 1 to 22, or X, Y, or M. The block_number is an integer based on the integer division of the chromosome position (POS // 1000000). So, when CHR and POS are provided in the request, and the Beacon instance knows the type of data requested (count of samples or allele frequency), the software determines potential file paths for visible datasets and checks the files for matching POS-REF–ALT rows. The list of visible datasets is determined at the arrival of the HTTP request.

Regarding the size of the Parquet files, for example, the data from this AFF1 synthetic allele-frequency dataset (22 chromosomes, 5.4 GB in total) is split and stored in 293 Parquet files, 423 MB in total using the highest compression.

The Parquet files are essentially tables with columns (for variant “sample count”: POS, REF, ALT, VT as variant-type, SAMPLES). An incoming Beacon variants request about the number of matching samples is mapped to the Parquet columns to determine the matching rows (column names are specified here in upper-case):

requestParameters: {

referenceName: CHR,

start: POS,

end: POS + REF.length,

referenceBases: REF,

alternateBases: ALT,

}

The count of matching samples (across all visible datasets) is computed from the filtered SAMPLES column values, which only reference VCF samples by index (e.g. 2,7-9 references samples “2,7,8,9”, which is counted as 4 matching samples).

The allele-frequency request is similar but expects a RECORD response, which is composed from the matching Parquet file row in the latest allele-frequency dataset:

resultSets: [

{

id: DATASET_ID

setType: "dataset",

exists: true,

resultsCount: 1

results: [

{

identifiers: {

genomicHGVSId: "NC_00000...:g.{POS}{REF}>{ALT}",

},

variantInternalId: "{uuid}:{REF}:{ALT}",

variation: {

location: {

type: "SequenceLocation",

sequence_id: "HGVSid:{CHR}:g.{POS}{REF}>{ALT}",

interval: {

type: "SequenceInterval",

start: {

type: "Number",

value: POS

},

end: {

type: "Number",

value: POS + REF.length

}

}

},

referenceBases: REF,

alternateBases: ALT,

variantType: VT,

},

frequencyInPopulations: {

source: "The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)",

sourceReference: "gnomad.broadinstitute.org/",

frequencies: [

{

alleleFrequency: AF,

alleleCount: AC,

alleleCountHomozygous: AC_HOM,

alleleCountHeterozygous: AC_HET,

alleleNumber: AN,

population: COHORT

}

]

}

}

]

}

]

Some values in the code above are computed on the fly (where curly braces are used within quotes). Also note that the output is about to be updated due to new cohorts information.

In summary, a “custom Beacon” developed for the node was based on:

- minimal data required for the User Portal,

- minimal endpoints required for the User Portal,

- file-based compressed and encrypted columnar data.

This “custom Beacon” is not to be mistaken with an “alternative Beacon solution” – it was just designed to match what the GDI User Portal expected to be implemented and it lacks many features expected from fully compliant Beacon solutions. In other words, if the GDI User Portal needs only a few “Beacon” endpoints from the nodes, it does not make sense to deploy a full Beacon solution with all the complexities.

FAIR Data Point – a data catalogue service

The data catalogue was introduced later in the GDI project with the intention to share information about the genomic datasets available in nodes. The GDI Estonia team evaluated the reference implementation and also a custom-developed solution. Again, here the development team finally switched to the custom version, since it was easier to customize (and MongoDB could be avoided).

One of the primary goals was to publish dataset records and withdraw them as quickly as possible after a user changes a dataset’s visibility in the local GDI Node system. In the final FAIR Data Point solution of Estonia, the only currently visible datasets are exposed through the API.

The data catalogue implementation of GDI Estonia is based on several specifications:

- service: FAIR Data Point

- data-model: HealthDCAT-AP and DCAT-AP

- response formats: RDF Turtle and JSON-LD

- validation: Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL)

The solution provides relatively easy templating support for rendering the RDF responses based on the properties stored in the local relational database. This gives developers confidence that they can easily introduce changes to the service in case the central data model is updated with new fields. (Of course, sometimes introducing new fields also means that the entire data-flow from the provider to the FAIR Data Point services must be reviewed and updated.) However, the main benefit of the custom FAIR Data Point service is that it’s entirely automated and does not require humans to edit the dataset metadata records. Only the list of catalogues is maintained by the NCP.

Developing the GDI-EE node

The story so far highlights the importance of understanding one’s local situation, including available services and resources, stakeholders, expectations, and requirements for all nodes. The team of GDI Estonia started by deploying and experimenting with the GDI starter kit, only to realise that it didn’t provide a cohesive solution that the team expected. The missing crucial piece was the data management solution for the node. However, data management revolves around organisations and local requirements (not just specific products). Therefore, it was clear that a custom node management solution is a necessity, and that it was not expected to be a universal solution that would be suitable to all GDI nodes.

The Business Process

We used SIPOC to analyse the business of the potential GDI node, gather requirements, and design technical services (MVP) supporting the business processes.

- Onboarding data-providers – registration of organisations and users for managing their GDI datasets.

- Dataset creation – data-provider’s steps for producing a dataset package file to to be registered at the node.

- Dataset life-cycle management – operations that data-providers can do with their registered datasets.

- Data discovery and access – when and how the node’s system exposes dataset properties to the central User Portal to enable researchers to find and request access to the data.

- SAPU preparation – how the node coordinates the setup of research environment with the requested data.

- Analysis in SAPU – researcher’s workflow for performing its work and obtaining results.

- Helpdesk – general business tasks for the node.

To support the processes 1-4, the Estonian GDI node offers a simple self-service portal (https://gdi.ut.ee/portal/) for data providers to manage their users’ access and to control their exposed datasets. The API of the node (excluding Beacon APIs) has been documented here.

Metadata of Genomic Datasets

One of the most challenging questions was defining the data stored in the node and the scope of the datasets. Although combining genomic data with patients’ records from health registries would have been the dream goal for researchers, we realised during the project that this is not feasible within the current project. EHDS took longer to be approved, and its technical services were not yet operational. On the other hand, linking the genomic data to health records would have made our system even more sensitive (the system currently doesn’t track the national ID codes of the data subjects). Therefore, once again, the team downgraded the solution to the minimum viable product (MVP) with minimal viable data. As the node’s primary data publishing scenario was the output of the Genome of Europe project, the system needed to support only three attributes per individual: biological sex, country of birth, and age. These properties do not change over time, making it easy to convey this information about each sample in an additional Parquet table as part of the dataset. No data linking is yet available with national healthcare systems to avoid the resulting complexities.

This is how the team finally defined a local dataset for the GDI:

- A set of genomic files: VCF, gVCF, and potentially also CRAM, BAM, SAM, FASTA, FASTQ, and/or infomaterials in plain-text or PDF.

- A set of properties describing the data: title, description, keywords, and optionally references to past versions that the dataset supersedes.

- A set of Beacon files (described above in the Beacon section).

- In case of variants, a Parquet file describing the samples.

The team developed a command-line tool for composing a dataset package for the GDI node. The tool verifies the dataset requirements, helps extract Beacon data from referenced VCF files, and composes the Parquet files. Finally, all the delivered files (excluding the original genomic files) are packaged into a TAR file and encrypted using the public Crypt4GH key of the node.

One of the data provider’s users uploads the file to the national node, where the package will be decrypted, verified again, and the extracted files will be saved in the node. Later, the user can control the state of the dataset – either remove it or make it visible to the GDI User Portal. The latter process will generate and assign persistent identifiers for the dataset and its files. The data management also supports making the dataset invisible to the central user portal and archiving (Parquet files will be removed, but dataset metadata will be kept).

Technical Services

Overall, the developed system consists of the following custom services:

- frontend for authenticated users (system administrators and members of the data-providing institutions)

- API backend for supporting the frontend and also for exposing the FAIR Data Point

- pipelines runner – a background service that runs dataset life-cycle pipelines.

- minimal Beacon – a service, deployed in two scenarios: allele frequencies (public) and sample counts for a variant (restricted).

All these custom services were written in Python, which is one of the top programming languages according to the TIOBE index. The frontend was written in JavaScript and is based on the Vue.js framework.

The system uses the following third-party data storage solutions:

- PostgreSQL for system records

- S3 (MinIO) for files

- Apache Kafka for system events

- HashiCorp Vault for secrets (including data encryption and decryption)

It is also noteworthy that the local GDI node data management system relies on some external services:

- national authentication portal (TARA) – local authentication of data-providers and system administrators;

- email server – notifications for users;

- HPC SAPU – restricted research environment (per research project).

- Life-Science AAI for authenticating sensitive Beacon requests is yet to be implemented (depends on the readiness of the GDI User Portal).

Deployment of the Node

All the software components are delivered to the target environment as Docker container images. Except for some external/existing services, most of the components are deployed on the HPC Kubernetes namespace using kubectl and Kustomize (Kubernetes native configuration management). Continuous delivery is supported by build-pipelines and ArgoCD, which automatically updates images on Kubernetes.

We have taken special care to ensure that the software does not run with root privileges and that it operates the container file system in read-only mode, allowing data changes only in volume directories. Sensitive parameters are kept in Kubernetes and Vault secrets.

The custom-developed software does not consume lots of resources: minimally it requires just 1 GB of RAM, at least 4 CPUs, and a few gigabytes of disk space. However, some third-party services need more resources; especially the Apache Kafka cluster, which in our case requires about 4 GB of RAM and 15 GB of disk space.

Here is the summary of the exposed GDI-EE endpoints:

- https://gdi.ut.ee/ – the public website

- https://gdi.ut.ee/portal/ – the frontend for local data management

- https://gdi.ut.ee/api/* – the backend API for the frontend

- https://gdi.ut.ee/system/* – general endpoints about the system (version, health, public key)

- https://gdi.ut.ee/fairdp – the root endpoint for the FAIR Data Point

- https://gdi.ut.ee/beacon/aggregated/v2/ – the root endpoint for the Beacon of allele frequencies

- https://gdi.ut.ee/beacon/sensitive/v2/ – the root endpoint for the Beacon of variants data

Conclusion

The team of GDI Estonia began by testing the starter kit products and also gathering expectations and requirements from the local stakeholders. Comparing the outcomes, it became clear that deploying the existing products was not feasible without straightforward business processes being defined.

The starter kit products are not cohesive enough to make node management easier for the people. The team learnt from the pain of setting up the products to avoid the mistakes when developing their own custom solutions. The team realised that a GDI node is not just about the services exposed to the User Portal. Instead, the node is about local data management for the GDI User Portal. The data ingestion and egestion processes were completely missing from the GDI starter kit, and that was the core feature that the team set out to develop.

Re-implementing the FAIR Data Point and Beacon data services around the well-defined core processes became easier after realising what API endpoints were crucial to the User Portal (rather than implementing all possible features mentioned in the product specifications).

GDI Estonia also decided to totally skip some of the services defined in the starter kit. The primary argument behind that decision was understanding the incapacity to run and support these services, as they did not match our local expectations. Taking advantage of the benefits of the status quo, the team was able to redesign the business processes to tackle the original needs defined by the GDI.

This is the key advice that the team can highlight from their experience: always build your GDI node around your local capabilities. Don’t implement a GDI node by forcing local partners to adapt to unfamiliar workflows imported from the GDI project or other nodes. Understanding what the central GDI services expect from nodes, it’s not actually that hard to gradually add support for new endpoints.